Customer Reviews

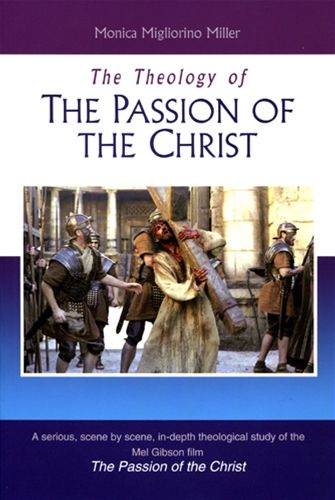

THE THEOLOGY OF "THE PASSION OF THE CHRIST"

Description

THE THEOLOGY OF "THE PASSION OF THE CHRIST"

Author: Monica Migliorino Miller, PhD

Copyright: 2005

First Printed: 01-31-2005

Reprints: 2005, 2006

A serious, scene by scene, in-depth theological study of the Mel Gibson film The Passion of the Christ, Dr. Miller’s analysis not only focuses on the more obvious Marian, Eucharistic and Incarnational themes, but she also discusses and explains the more difficult images and gestures of the movie such as the demon child held by Satan, the donkey carcass behind Judas, the raven above the thief’s cross, etc. Written in a very reader-friendly style, the book also discusses the film’s depiction of the Jews and Romans from a theological and cultural perspective and examines the various sources of The Passion, notably theDolorous Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ by Anne Catherine Emmerich. One chapter examines how the movie has changed people’s lives and an Appendix compares The Passion of the Christ to other movies about the life of Jesus.

“For the many devout Christians who were deeply moved by the film The Passion of the Christ, Dr. Monica Miller’s book will be an excellent guide to discussion. Her work is filled with serious questions, answers, and details about the film and its relationship to the traditional Christian theology on the sufferings and the death of Our Lord. If you were touched by the film, you will find this book enlightening and a source of much meditation.” Father Benedict J. Groeschel, CFR

About the Author: Monica Migliorino Miller, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of Sacred Theology at St. Mary’s College of Madonna University in Orchard Lake, Michigan. This is her first book for Alba House.

Book: 200 pages

ISBN: 978-0-8189-0975-7

Prod. Code: 0975-7

Reviews

"Mel Gibson's Passion film of two years ago, besides directly affecting the millions who found it devout, also occasioned a myriad of religious artistic, and political pro-and-con reflections. Monica Migliorino Miller's The Theology of "The Passion of the Christ" considers many of these from her own conviction of the film's excellence. She has done her work well, with fairness and impressive thoroughness. She merits a good many readers, and most of those readers will find themselves appreciating the art and devotion of the film even more than before." --Philip C. Fischer, S.J. in Review for Religious, February 2006

"Monica Migliorino Miller draws on a wide range of published critical comment to present an apologia for Mel Gibson's film on the Passion, at the same time skillfully refreshing one's memory of the film. Into this, with theological competence and spiritual insight, she weaves reflection on the significance of the sacrifice of Christ for the human story." --Francis Cardinal George, OMI, Archbishop of Chicago

"For the many devout Christians who were deeply moved by the film, Dr. Monica Miller's book will be an excellent guide to discussion. Her work is filled with serious questions, answers, and details about the film and its relationship to the traditional Christian theology on the sufferings and death of Our Lord. If you were touched by the film, you will find this book enlightening and a source of much meditation." --Father Benedict J. Groeschel, CFR

"With critical as well as theological insight, Monica Miller cuts through the confusion behind much of the controversy over The Passion, from fastidious objections to its emphasis on blood and suffering to misguided complaints about its lack of concern with ordinary dramatic notions of character development and plot structure. Miller decisively refutes the critics who failed to see the religious meaning of Gibson's film, and opens new worlds of meaning for appreciative viewers wishing to enter more deeply into The Passions's mysteries." --Steven D. Greydanus, Film critic, National Catholic Register & DecentFilms.com

"Even before Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ was released on DVD, books about the film began to emerge.The Theology of 'The Passion of the Christ' by Monica Migliorino Miller, presents a serious, scene by scene, in-depth theological study of the movie. Miller writes, 'The Passion of the Christ is not simply a movie -- it is a religious experience.' Miller explores the theology underlying Gibson's use of Mary, who 'is central to the drama of the film.' She explains how Gibson uses Genesis 3:15 as the lens through which he views Jesus' mother: 'She actually contributes to the overcoming of the Evil One.' Miller continues: 'Mary is there to support her Son, even to protect Him and to aid Him to accomplish His salvific task.' In Chapter 3, Miller presents the themes of the Incarnation that she finds in the movie. But by far the most helpful chapter -- six -- presents the sources of The Passion. In painstaking detail Miller lists every scene of the movie and explains which ones come from each of the four Gospels (along with the appropriate notation), the Stations of the Cross, and Anne Catherine Emmerich's The Dolorous Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ. Emmerich, an 18th-century stigmatist, was beatified on October 3, 2004 by John Paul II. As Miller explains, Emmerich's work expresses the very popular theological perspective 'known as the satisfaction theory.' She says, 'In this theory, consistent with St. Anselm, God is a God of mercy, but also a God of justice. He cannot just forgive sin, but the balance of injustice must be 'satisfied.' Jesus takes the sins of the world upon himself and the punishment for sin -- namely death. Jesus' death is a free offering. He freely offers himself up as a sacrifice for sin.'" --Rev. Mark G. Boyer in The Priest, December 2005

Mel Gibson gave the commencement address at Loyola Marymount University in 2003, amidst brewing controversy surrounding his now famous film, The Passion of the Christ, almost a year before its actual appearance in theaters on Ash Wednesday of 2004. There were bodyguards everywhere and security was tight; threats had apparently been made on Gibson's life. Truly, when one seeks to do the will of God -- more precisely, when an artist like Gibson sets out to create a genuinely devotional work of sacred art -- the powers of darkness gather in opposition. But Gibson made his film, which has gone on to spectacular successes on all fronts, except in the profane arena of mainstream Hollywood, and, on that sunny day in early May he delivered his commencement address to a throng of graduates, their families and university faculty.

It was a unique event, dramatically different from all the other dozen-plus commencement addresses I have attended in my capacity as a professor at LMU. Gibson, obviously self-conscious and nervous, spoke to our graduating seniors not of future riches and glory but of the hardships and sufferings that life holds in store, and he spoke to them of God, of keeping the Faith, and of his own life in this regard. He spoke of his past, his sins, his wanderings, and then his return to the Faith. He spoke of God's forgiveness. He spoke of the imperative to stay with God, to keep the Faith.

He delivered his remarkable address against a backdrop of an apparent majority of cynical and condescendingly smiling faculty, and a foreground of, I imagine, largely confused students. But this was about the students' future, so Gibson's seeds of faith may, by the grace of God, flower forth some day in profound ways.

His movie similiarly stands out as a sign of contradiction vis-à-vis the prevailing genres of Hollywood movies. Here, too, Gibson answered a call to use his gifts in the service of his God and his Faith, and The Passion of the Christ will surely bear abundant spiritual fruit.

The movie defies classification in ordinary cinematographical terms, and it cannot really be judged in comparison even to other films about Christ. It is of an altogether different order. It is a devotional piece and a source for meditation on and contemplation of the Passion of Jesus Christ. And this is the central thesis of the book under review by Miller, a Catholic theologian on the faculty of St. Mary's College of Madonna University in Orchard Lake, Michigan. Her book is a compactly written and beautifully argued exposition of the theological motifs that permeate Gibson's magnificent work of devotional art, and is filled with marvelous insights. For example, the following passage: "In The Passion Jesus indeed overcomes the Devil by the pouring out of His blood. Moreover, as His whole body is covered by the wounds of His Passion, Christ literally wears a cloak of blood. On the feast days of martyrs a priest's liturgical vestments are red. Jesus, in the film, does not simply wear a symbolic color of blood. He wears blood. He is dressed in blood because He is the true priest and the true sacrifice.... Soaked with blood, carrying His cross, Jesus tells Mary, 'See, Mother, I make all things new.' This line, adapted from Revelation 21:5, is uttered about half-way through the movie and indeed it is the center, the key to the Gibson film. By His blood Christ makes all things new."

This book's effect on me was unexpected: I had imagined that, having seen Gibson's film and having been spellbound by it, I would find the book to be something along the lines of an analysis, dry in the usual academic sense. Instead, I found a sequence of crystal-clear lectures by a Catholic woman who saw so much more and who is on fire with the zeal to inform others about what Gibson's film achieves in terms of theology. She delineated surprising details of the film and charted depths I hadn't realized were present -- so much so that I must see it again and witness Gibson's rendition of the Passion at a more profound level.

Miller has done a wonderful service for all who would watch Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ, whether it be for the first time or not. But those who come to it for the second time after reading the book are in the most enviable position of all. --Michael Berg in New Oxford Review, September 2005

When an artist is faithful to his subject, his art can contain depths he never sought to incorporate. Such is the case with Mel Gibson and his 2004film The Passion of the Christ. As screenwriter and film critic Barbara Nicolosi notes in her preface to Monica Migliorino Miller's The Theology of the Passion of the Christ, even Gibson himself found that he had difficulty explaining to skeptical viewers the significance of certain scenes in his film. "Explaining why the image [of the ugly baby] affected us all so strongly is the job of the theologian," Nicolosi comments.

In undertaking that job, Miller examines various theological themes of The Passion, particularly the uniquely Catholic Marian and eucharistic themes. Reading Miller's observations on these themes will enrich future viewings of the film by those who, like Gibson, know there is rich meaning to the film's images but have difficulty explaining exactly what they are seeing.

Gibson's Mary, in contrast to other cinematic portrayals of the Blessed Mother, is actively involved in her Son's Pasison, to the extent that one chagrined Evangelical Protestant pastor sarcastically noted that "they should have named the film The Passion of Jesus and Mary. Such a thought obviously horrified him, but a Catholic would nod in agreement and find the suggestion apt. As the prophet Simeon predicted (Luke 2:34-35), Mary suffered alongside her Son, a detail finally fully captured on film by Gibson and noted by Miller. Among the powerful scenes used to show Mary's suffering are her presence at Christ's scourging, her retrieval of his eucharistic blood spilled by the scourging, her accompaniment with him on the via dolorosa in counterpoint to Satan, and her active participation at the foot of the cross that culminates in her pleading with her Son to allow her to die with him.

Miller, originally mildly critical of the violence in The Passion has since pondered the film's bloodiness more deeply and drawn out more completely its theological significance. She cites a reviewer of the film who noted, "The Passion isn't just a gruesome movie but a ritual that exalts the blood of Jesus because the release of this blood released humanity from sin." Skeptical critics of the movie saw the blood as just so much blood. But the faithful recognize that the precious blood of Christ is salvific and eucharistic. Glorying in that blood is the opposite of the "sadomasochism" the film's critic allege; it reflects instead a deeply Christian joy in the source of human salvation.

Miller explains well, in opposition to the claims of critics, that the movie is biblically based, but that it also draws upon the visions of Christian mystics, especially the recently beatified Anne Catherine Emmerich, as recorded in her book The Dolorous [i.e., Sorrowful] Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ. Although many critics dismissed the movie because of its dependence for artistic detail on the writings attributed to Emmerich, Miller explains that interpretations of the Gospels are common to other Jesus movies and plays, such as The Last Temptation of Christ and Jesus Christ Superstar. What should matter is not that the Gospels are interepreted but whether they are interpreted in a manner faithful to orthodox Christian tradition.

Although Miller is evenhanded in her treatment of the controversial issues surrounding Emmerich -- including that Emmerich's writings were to some extent influenced by the anti-Semitism of her time and culture -- it would have been helpful from an apologetics perspective to explain the role of private revelation in the Catholic faith. It is also important to understand that the writings attributed to Emmerich are believed to have been highly embellished, perhaps even falsified, by Emmerich's secretary M. Clemens Brentano to such an extent that Emmerich's cause for sainthood was delayed for nearly a century and progressed only when the Church excluded the writings attributed to her from consideration of her life. Thus, though it is unobjectionable for Gibson to have drawn neutral material from these writings to flesh out his adaptation of the Gospel accounts of the Passion, the writings themselves cannot be considered authoritative.

Unlike many movies produced today, Mel Gibson's The Passion seems destined to become a movie classic that each new generation will experience as a cinematic rite of passage. In contract to such secular predecessors as The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind, may be the first religious movie to attain such a distinction. And when new viewers approach The Passion of the Christ, they will find The Theology of the Passion of the Christ to be a handy guide to the theological meaning of the images they experience in the movie. --Michelle Arnold in This Rock, July-August 2005

"The Passion referred to here is Mel Gibson's now famous and controversial film version. Miller, an associate professor of theology at St. Mary's College of Madonna University in Orchard Lake, Michigan, is entirely positive about Gibson's artistic rendering but wants also to provide a theological analysis of what the filmmaker has done. While readers may differ about her enthusiastic perspective, she does the service of discussing the theological implications and putting them into perspective. She also documents the fact -- often obscured in some of the discussions of the film -- that much of its inspiration and content come not from the Gospel but from medieval mystic Catherine Emmerich and other postbiblical sources." --Donald Senior, C.P. in The Bible Today, May/June 2005

"Monica Miller has done an important service to the People of God by considering The Passion of the Christ as a source of theology. Pushing beyond the political, social and even ecclesial controversies that must always accompany the Cross as the Sign of Contradiction, her book asks us all to reverentially regard the film, and allow it to deepen our understanding of the mystery of Calvary. It is a humble task for a Catholic theologian to be led by the ruminations of a contemporary artist--and, how much more, one from Hollywood?!--but, in so doing, Miller sets an example of exactly what the Pope means in calling for 'a renewal of the fruitful dialogue' between the Church and the arts.... In affirming the theology that underlies the project, Dr. Miller has listened to the voice of the artist, and to the voices of the sheep. Her work goes a long way to demonstrating that The Passion of the Christ 'worked' with believers for one reason: it brought them into an encounter with their Shepherd in His most compelling posture as the Lamb of God." --Barbara R. Nicolosi in the Preface to the book.

"Passion" scene by scene: When Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ was released last year, the theological and cinematic stir it created was felt far and wide. A deeply thoughtful and religious experience, the film is a moving picture of the historical event with which we are all familiar. Monica Migliorino Miller, Ph.D., an associate professor of Sacred Theology at St. Mary's College of Madonna University in Michigan, breaks down the movie in The Theology of "The Passion of the Christ": a serious, scene by scene, in-depth theological study of the Mel Gibson film."In the book, she discusses -- in a very readable way -- the Eucharistic and Marian imagery found throughout the film, as well as the powerful images that are part of the story (the dead donkey, the images of Satan, etc.). Not a cinematic review nor a technical discussion, the first four chapters discuss those theological meanings of the images and scenes in the film. The fifth chapter looks at the sources of the movie's theology. And the last chapter focuses on the reaction of moviegoers and why the movie provokes such a reaction." --Crux of the News, April 25, 2005

Here's an accessible exploration of the biblical basis and spiritual writings that underlay the Mel Gibson film. (Skip this review if you have to ask, "Which Mel Gibson film?") Monica Migliorino Miller, an associate professor of sacred theology at St. Mary's College of Madonna University in Orchard Lake, Michigan, "sets an example of exactly what the Pope means in calling for 'a renewal of the fruitful dialogue' between the Church and the arts," notes Barbara Nicolosi, Catholic screenwriter and Register columnist, in the Introduction. It will be plain to even casual readers that Miller, who holds a degree in theater arts, is a fan of the movie. "The Passion is a religious meditation -- celluloid is simply the medium," she writes. Her work here primarily addresses the theological ramifications of the film but she also includes a chapter on the movie's sources and one on the reactions it has engendered, along with an appendix that includes comparisons to other movies about Christ.

Miller focuses on several key points: Mary's role in Christ's passion, the biblical basis of Gibson's Passion, charges of anti-Semitism against the movie, and Gibson's reliance on the writings of mystic and stigmatic Anne Catherine Emmerich. "The Passion is a rare film because it is truly theological in the classical sense," she writes. "The word 'theology' means study of God. Classical, authentic theology is faith seeking understanding -- or intellectual worship."

The book's most powerful chapters deal with Mary's role as interpreted by Gibson. Her weakest moment comes in the honest admission that Emmerich's visions exhibit at least one anti-Semitic moment and her tepid explanation that even mystics are a product of their age. "The contributions Emmerich makes to Gibson's 21st-century movie cannot be over-emphasized," Miller writes, adding that she does not believe Emmerich was anti-Semitic. "There is very little in Emmerich's visions [indicating] that she believed in or defended the collective guilt of the Jews," she writes.

Miller's chapter dealing with Mary's role in Christ's passion demonstrates in an especially thought-provoking way that Gibson's view of Mary is radically different from that of previous filmmakers -- most of whom portrayed Mary as an overwhelmed, essentially passive bystander. "Mary, in the Gibson film, is the only other character besides Christ who actually sees Satan," Miller points out. "Mary alone sees the Devil. Their eyes meet. The moment of the ancient enmity has arrived. Mary is there to support her son, even to protect him, and to aid him in his salvific task," she continues. "Indeed, almost as soon as Mary sees the Evil One she turns her attention back to Jesus, almost as if she were aware of the danger to her son by the presence of Satan. It is then that Mary asks John to find a way to bring her closer to Christ." This understanding of Mary as active in the redemption of the world is more consistent with Catholic doctrine than the helpless icons of most previous film interpretations.

The Theology of "The Passion of the Christ" adds to our understanding and appreciation of the movie and, in doing so, helps illuminate aspects of Jesus' passion and death for us. Which is to say that, heading into Holy Week, it's an ideal read. --Valerie Schmalz in National Catholic Register, March 13-19, 2005